Welcome back to the Lovecraft reread, in which two modern Mythos writers get girl cooties all over old Howard’s sandbox, from those who inspired him to those who were inspired in turn.

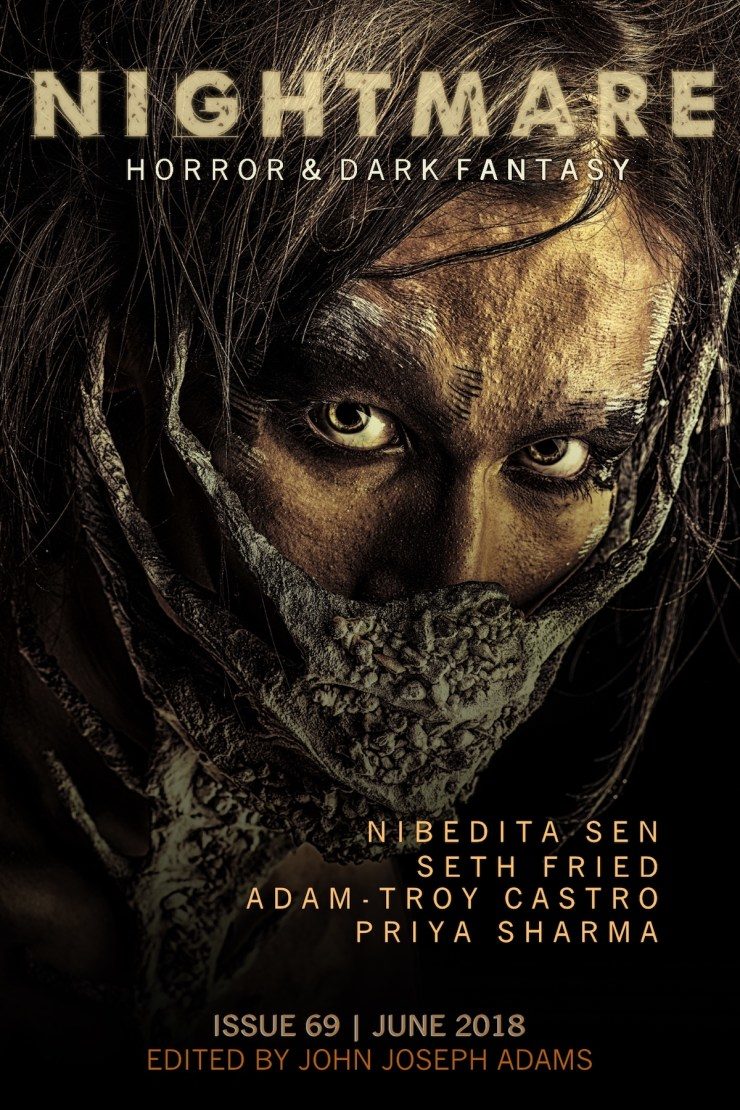

This week, we’re reading Nibedita Sen’s “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep,” first published in the June 2018 issue of Nightmare. Spoilers ahead (but go ahead and read it first, because it’s both short and awesome).

“7 Rivers: Troubled night. Heard whalesong through the portholes before sleep and thereafter continued to hear it in my dreams. It is hardly unusual to hear whalesong in these waters, but this was of an uncanny and resonant nature; deep elongated beats that that seemed to vibrate in my marrow and bone.”

Summary

Being the journal of Captain James Bodkin, commander of the whaling vessel Herman. The Herman’s current voyage has been sponsored by the Guild of Natural Philosophers; Arcon Glass, the scientist on board, claims he seeks a solution for the overfishing of whale routes that threatens the industry’s future. Bodkin can only approve such a purpose, and Glass’s intimation that the Guild might publish any future memoir inspires Bodkin to devote himself to his journal with an enthusiasm he hasn’t felt in years.

The first whale harvested is a cow with calf. Bodkin describes her capture and butchering in frank, bloody detail. One crewman is lost in the hunt—such is the hazardous nature of their profession, but his widow will be compensated. Glass loiters on deck as the crew strips and renders blubber. He seems disgusted by the process, which surprises Bodkin. Shouldn’t dissections have inured a Philosopher to such visceral messes? But the bespectacled, mincing fellow persists in fussing amidst the work. He’s laid claim to the cranial sac containing valuable spermaceti oil. Not the oil itself, just the sac, which he fears the crew may puncture in removing the spermaceti. Once he procures the sac, he treats it with chemicals to produce a huge, tough bladder, for what purpose who knows?

The orphaned calf follows the ship, but it can’t be responsible for the whalesong that resonates through the night, uncanny deep beats and high chirrups. If Bodkin didn’t know from experience how water and timber can distort sound, he might think the wailing came from inside the hull.

Piqued by the failure of a second hunt, a crewman kills the calf. Glass claims its spermaceti sac as well. Shortly after, Bodkin discovers the source of the strange whalesong: Glass has suspended his cured sacs and filled them with wax and glycerin. Wires connect the sacs to small drums; with a special instrument, which Glass presses to the sac wall, he can reproduce the music of the whales. Bodkin doesn’t see how this invention can ease the overfishing situation, but he doesn’t interfere with Glass’s experiments.

Buy the Book

Middlegame

Glass is soon “issuing forth a veritable orchestra of different sounds that uncannily mimic the [whales’] calls.” The incessant “concert” makes the crew uneasy, especially surgeon Baum whose sickbay is now Glass’s workroom. Bodkin admits that listening to the simulated whalesong “causes a great pressure and dizziness to swell in my skull.” Were he not loathe to approach the workroom, he might order the fellow to desist.

The Herman sails further north into regions of snow squalls, fog and ice. After the first two kills, they have no more luck. Morale falls, and Bodkin fears his last voyage may end in defeat. Glass comes to his cabin with brandy and reassurances. The whales are intelligent, he says, capable of communicating with each other. Think how an industry that’s mastered their language could lure whales right to its ships, even establish hatcheries to breed up plentiful stock! There’s more—the Guild believes that in the far north there are leviathans, whales far bigger than any yet harvested. So push north, beyond latitudes any ship has explored before, and with the aid of Glass’s song-machine the Herman will make history!

Bodkin’s persuaded. Glass brings his machine up on deck. Meanwhile an odd phenomenon dogs the ship: water black as ink beneath the hull, oval-shaped, a shadow they can’t shake. A crewman disappears. If he jumped overboard, Bodkin can’t blame him, for he too begins longing for cold water, to sink into it and “joyfully expel the breath from his lungs.” The beautiful music comforts him now, though its frantic production seems to take a heavy toll on Glass.

Stark white ice cliffs rise around the ship. The water is black, but blacker still is the shadow beneath the hull. More crewmen disappear in the night, and the ship’s surgeon dies after flaying the skin and fat from his own arm. The first mate tries to rouse Bodkin from his cabin retreat, where he goes on writing though his fingers grow clumsy, like a fluke, and his head so heavy. Crashes and gunshots sound from the deck above. Glass screams. What has the first mate done? Why didn’t Bodkin do it sooner? After a silence, whalesong resumes, but from the water this time, and louder than any of Glass’s songs.

When Bodkin finally comes up on deck, he sees Glass and Law “in the sea, the foam rushing over their grey backs.” Other “shapes of the crew” crowd and sing in the waters as well, pacing the ship. And now Bodkin realizes what the black shadow under the hull is: an eye, “her eye, benevolent and gentle and wise.” Bodkin will go to her when he finishes writing. He must get down one more thought, for when he and crew migrate to warmer waters to breed, they’ll be unable to speak to any whale ships they meet.

They—he—will be unable to do anything but sing.

What’s Cyclopean: That eye!

The Degenerate Dutch: No strong distinctions among human groups this week, but a pointed reminder that we don’t always recognize—or respect—intelligence where we find it.

Mythos Making: The ocean is vast and full of unknown creatures, whose power we’d do well to appreciate… perhaps from a greater distance.

Libronomicon: Captain Bodkin keeps a record of his voyage, though he struggles to summon enthusiasm for the task. A man must have a mind to what he leaves behind.

Madness Takes Its Toll: Is Glass a madman or a genius? Certainly his research takes a toll on him: His hair is falling out and his color is grey and sickly.

Anne’s Commentary

Just in time for the 23rd Annual Moby-Dick Marathon at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, we are reading Sen’s “Leviathan Sings to Me in the Deep,” a story inevitably reminiscent of Melville’s masterpiece. I’m thinking that the name of Sen’s ship, the Herman, is a nod to Melville. I was also thinking, from the first page of “Leviathan,” that we weren’t in Kansas anymore, or New Bedford, or even Nantucket, but in a world with strong whaling parallels to our own. What are these strange month names, Harvest and Rivers and Wind? What’s this Guild of Natural Philosophers? To what do they nod?

Luckily for me, Sen discusses her inspirations for the story in a Nightmare Author Spotlight. The first, she writes, was her fascination for whales and their music, “so serene, and beautiful, and painfully, painfully in contrast to the violence we’ve visited on them.” The second was the video game series Dishonored, which is “set in a world built on a massive whaling industry, with its technology powered by volatile, frosted blue-white canisters of thick whale oil, magical charms carved from whalebone, and an enigmatic god who lives in a void where whales swim among the inky black.” Now I have my bearings. Not that I needed to know about Dishonored to follow “Leviathan,” for it stands sturdy on its own. However, recognizing the Dishonored connection allows me to hear inspiration calling to the work inspired, like whalesong to whalesong echoing through the depths, enhancing appreciation.

The recognition also makes me recognize, more acutely than usual, an inherent danger of reading for this blog. The Lovecraft Reread has expanded to Lovecraft and Company, embracing not only the canon and collaborations but those writers who influenced Howard and who have been influenced by him, to emulate or expand or rebut. And so, do I tend to go into each new story looking for things Lovecraftian? Why yes, I do. Lovecraftian elements can be obvious, as in borrowed Mythos lore, or subtle, matters of atmosphere or theme, as in that “cosmic” outlook of his: Man is insignificant in the universe (horror!), but he’s far from its only intelligence (horror again, and/or wonder!) Frankly Mythosian tales are legion. The subtle notes reverberating through the literature of the weird, the spider-threads of connection and conversation pervading the genre, are legion to the nth degree. But those do and should resist labeling. At least labeling of the sticky reductive sort.

And my point is, reductively: Not every Leviathan (undersea god or monster) is Cthulhu. Or Dagon, or Hydra.

Not taking my own point, I went into Sen’s “Leviathan” assuming it would be Cthulhu, or Dagon or Hydra. Which led me to believe that Arcon Glass (odd-looking to begin with, and increasingly odder) must be a sort of Deep One. I also read all his interactions with the Herman crew as devious. Here was no ordinary operative of the Guild of Natural Philosophers—here was a whale-mole undermining the industry he supposedly served! Glass meant all along to summon Cthulhu (Dagon/Hydra), to sabotage the whaling voyage by turning all the whalers into homocetaceans like himself! It’s like how, in “The Temple,” Lovecraft uses a ship’s log to follow the overthrow of mere human aggressors by ancient forces—there the German submarine crew turned porpoise-like by sea-deities. Or like how, in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” Lovecraft’s narrator turns from Deep One antagonist to Deep One himself, and why not, since as old Zadok tells us, ultimately we all come from the ocean and can return to it only too easily.

Or it’s not like “Temple” or “Shadow,” in that I don’t think Sen had either of those stories in mind when she wrote “Leviathan.” Yet “Temple” and (especially) “Shadow” do converse with “Leviathan,” in the grand salon of weird fiction, on the enduring and expansive topic of transformation. Transformation via genetics or magic, via biological fate or goddess-inspired empathy turned identification on a somatic level.

And, in the grand salon, “Shadow” and “Leviathan” pose without positively answering the question: Is this transformation, this shedding of humanity in both cases, a good thing? Lovecraft’s narrator realizes he goes to punishment in Y’ha-nthlei, but hey, eternal glory will follow! So he allows dreams to assure him. Sen’s Bodkin looks forward to going to the “benevolent and gentle and wise” owner of the eye that’s followed the Herman, but he does experience a last misgiving about what will happen when he and his whalish crew encounter whalers who won’t recognize them, won’t be able to understand their new language of song.

Makes me wonder whether the giant eye is benevolent after all. Just saying: What could be sweeter revenge for the “enigmatic god” of the inky void than for our former whale hunters to be hunted as whales?

The irony indeed!

Ruthanna’s Commentary

We’re back at last, after a break for holidays and Medical Stuff. None of which involved experimental surgery for creating gills, we promise. Moving on, we’ve got one hell of a story to kick off the new year! Nibedita Sen described this on Twitter as “a Lovecraftian whaling ship story,” which is the sort of summary that will get my attention every time. (She also mentioned in the same tweet that she’s Campbell-eligible this year—and if “Leviathan” is any indication, Campbell-deserving too.)

My first thought in response to “Lovecraftian whaling ship story” was CTHULHU GETS REVENGE, which would have been a perfectly fine thing—I’m always happy to see whales saved with great force. Instead we get something subtler and cooler: a sort of unholy hybrid between Moby Dick, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” and “From Beyond” (or any of a dozen other stories about scientific experiments that transform the experimenters).

I’m a child of the 80s, so my reflexive associations with whalesong are Star Trek IV and meditation and the background music playing at Earth House while I shopped for rainforest-friendly desserts. But they are gorgeous and eerie and haunting, and only recently something you could listen to on a whim. They fill more of the world than any human music, and they come from a species with whom we spent centuries at war.

In the 80s we played whalesong on cassette, with hope and respect (if also, doubtless, with a tidy profit motive on the part of the recording studios). In Sen’s not-quite-1800s setting, scientist Glass plays those mournful calls on the bloody remains of the singers. Nor is he much like the Mother of All Squid in his methods—mother and child were slaughtered for meat and oil before their organs ended up in his appropriated sickbay. And his goal, ultimately, is to use those stolen songs to lure other whales to their doom. He and Captain Bodkin speculate about the intelligence demonstrated by the recorded songs, but don’t take the next, empathetic step that might tell them their “trap” is a terrible idea.

But this isn’t a story of bloody vengeance, Cthulhoid or otherwise. Nor is it a story of the sea’s inevitable dangers, of hungry leviathans and myths turned deadly. What happens to most of the crew, immersed in whalesong, is stranger than death. We follow Bodkin’s shift from shuddering at the songs’ eeriness to taking unambiguous joy in their beauty. Things that would have seemed terrible or impossible a few journal entries ago, he comes to accept as wondrous fact. His final transformation echoes that of the narrator in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” but here it’s not an inevitable consequence of heritage. Instead, it seems a fair trade for what they’ve stolen from the ocean. Perhaps Glass is right that his invention resolves the problem of overfishing, albeit not the way he expected.

I wonder if anyone does return alone to tell the tale. Perhaps only Bodkin’s logbook, a legacy raw and unedited. Or perhaps nothing so clear will make it back to shore. Perhaps there’s only a ghost ship plying the waves of the arctic, its siren song echoing across the waves, reverberating in the hearts of explorers who drift too near.

Next week, Lovecraft and Adolphe de Castro’s “The Last Test” offers yet another submission to the Journal of Bad-Idea Experiments.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. She has several stories, neo-Lovecraftian and otherwise, available on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna can frequently be found online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.

Like Anne, I strongly felt a connection to Dishonored. And that may have even created a tonal and emotional substrate that colored how I perceived the story. All to the good, I’d say, but certainly not necessary for enjoying the story. And also like Anne, I was reminded a little of “The Temple”. Sen may or may not be aware of that story, and I don’t think it matters. In Lovecraft’s story, the transformation was almost a release or a rebirth, while here it seems more an assimilation or possibly a punishment (much like the tale of Dionysos and the pirates, which we discussed in “The Temple”).

I’m more a child of the 60s and 70s, so my first encounter with whale song was the Judy Collins album Whales & Nightingales and then my awareness and perception of it grew pretty much along with that of the general public. I don’t know that all of that affected my reading here, because these whales seemed much more alien and not at all like our whales (maybe some of Dishonored creeping in again).

Also, isn’t there a Far Side cartoon which is essentially the final revelation of the great eye under the boat? Or maybe it’s Gahan Wilson. A quick search didn’t turn anything up (a few other giant eyes in Larson’s work), but I’m sure I’ve seen it. Fortunately, I didn’t think of that until just a few minutes ago.

Hope the Medical Stuff wasn’t too serious.

*scowl* Dagnabbit, I can’t abide stories where humans turn into aquatic creatures,* even whales in whaler-prowled seas. This one sounds good for other people to read, though. People who don’t share my affliction.

Yeah, I snickered at the Herman’s name.

You’re wise to promise that you weren’t getting and/or doing experimental gill-creation surgery. If you were, I would hunt you down and demand information. ” :-p

*Except Deep Wizardry by Diane Duane, because it’s the Bestest Most Beautiful And Perfect Novel EVAR.

By coincidence, I read this immediately after Adrian Tchaikovsky’s “The God of Profound Things” (in The Scent of Tears), another tale of a leviathan and its obsessed pursuers, and there are some interesting parallels between the two stories. Tchaikovsky’s leviathan is a gigantic Eurypterid (sea scorpion) that eats whales for lunch, but I can see a resemblance between it and Sen’s Mother of Whales, as well as between the two mad scientists fixated on them (and their ultimate fates).

As Bruce said, “Fish Whales are friends, not food!”

I… I can’t read this one. Whales being killed makes me really sick.

This is only parallely related, but have you all done a reread post for the Derleth story the Seal of R’lyeh?

https://talesofmytery.blogspot.com/2015/06/august-derleth-seal-of-rlyeh.html

If the definition of tragedy is that everyone dies and the definition of a comedy is that everyone gets married, the fact that Derleth basically wrote a Deep One Comedy makes me so happy.

Like, the doomed protagonist finds out he’s related to the deep ones and instead of being doom it’s wonderful because now he can get hitched with his deep one gf.

I want a reread post of this so bad…

@3: Oooh. *checks all of my libraries* Darn, I can’t get it anywhere.

“Transformation via genetics or magic, via biological fate or goddess-inspired empathy turned identification on a somatic level.” That about sums up the means for what I want. I begged for it in a poem roughly 13 years ago:

Return me to the water

Oh, let me leave the shore

For I am Uinen’s daughter

And I love the land no more

Give me fins and give me gills

However they may come

By secret rites or toxic spills

I care not where they’re from

Centuries in darkness I would wait

If that’s the needed price

If I must lose all to mutate

I’d make that sacrifice

In river, marsh, lagoon, or lake

Or sparkling azure brine

My lost birthright I want to take

Let syndactyly be mine!